10 Things I Hate About You is a film adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, updated to reflect contemporary times for it’s release in 1999. It stars young Julia Stiles, Heath Ledger, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, and Larisa Oleynik. And here, before even moving past the article’s introduction, is where I first started doubting the knowledge of its authors.

It leaves out Larisa Oleynik, who was one of the big names attached to the movie. The others went on to have big movie careers, but she was already an established television star with the lead role in a popular Nickelodeon show, The Secret World of Alex Mack (Graham). The article goes on to say that it was a breakout success for Stiles, Ledger, and Gordon-Levitt, but Gordon-Levitt was also already an established television star on 3rd Rock from the Sun (IMDb). While neither of these inaccuracies are huge, the second one is particularly interesting due to the citations given as support.

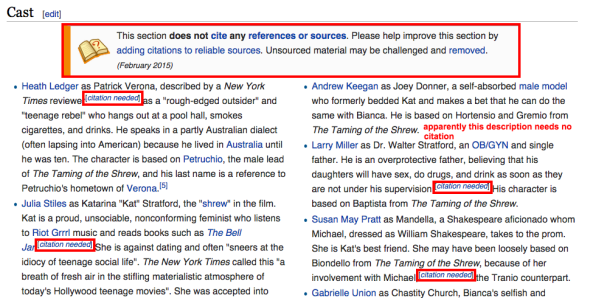

Notice that two of the three are referring to Stiles, which results in the appearance of a citation for each actor up above, but really leaves the claim about Gordon-Levitt unsupported. Furthermore, “Julia Stiles on ‘The Omen'” does not sound related to 10 Things I Hate About You, but the link is dead, so it is impossible to verify. (Incidentally, the link supporting the claim about Ledger requires a password to view the news site, so it may or may not be legitimate as well, but 10 Things as a breakout role for him lines up with my own knowledge on the matter). Citations continue to be an issue for this article, but they are only officially named as an issue for the Cast section.

The parts that have been picked out for citation make very little sense. For example, the basic character traits of Larry Miller’s character, Dr. Walter Stratford, are called out for citation, while a claim about Andrew Keegan’s character, Joey Donner, relating to particular characters in The Taming of the Shrew is allowed to stand unchallenged. This brings us to: who is deciding what is important to this page? The edit history shows that over one thousand distinct editors have made almost two thousand total edits, from the day the page was created in 2003 up through today, which was one of nine edits by six distinct editors in the past month. With that much fairly consistent editing*, I would have assumed that the page would be in spectacular shape. However, it clearly is not well verified, (aside from the already mentioned iffy citations, the closest they get to citing The Taming of the Shrew is citing the SparkNotes page) and I have far more quibbles over details than there is room for here.

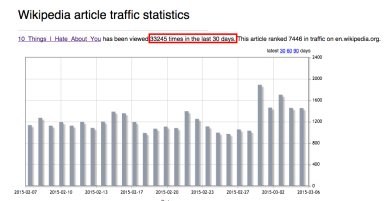

This brings us to: who is deciding what is important to this page? The edit history shows that over one thousand distinct editors have made almost two thousand total edits, from the day the page was created in 2003 up through today, which was one of nine edits by six distinct editors in the past month. With that much fairly consistent editing*, I would have assumed that the page would be in spectacular shape. However, it clearly is not well verified, (aside from the already mentioned iffy citations, the closest they get to citing The Taming of the Shrew is citing the SparkNotes page) and I have far more quibbles over details than there is room for here.  What’s even more surprising is the number of people who have viewed the page: over thirty thousand in the last month alone. When viewed in the context of the number of people receiving this information, the number creating it pales considerably. Collective intelligence, which is “the ability to pool knowledge and compare notes with others towards a common goal” as set forth by Henry Jenkins, begins to seem not so “collective” after all. (As a reminder: that’s about 1,000 editors over the lifetime of the page to over 30,000 views in the last month alone, which is not 30:1 – it’s more like 4000:1, assuming a steady viewing rate over the lifetime of the page.)

What’s even more surprising is the number of people who have viewed the page: over thirty thousand in the last month alone. When viewed in the context of the number of people receiving this information, the number creating it pales considerably. Collective intelligence, which is “the ability to pool knowledge and compare notes with others towards a common goal” as set forth by Henry Jenkins, begins to seem not so “collective” after all. (As a reminder: that’s about 1,000 editors over the lifetime of the page to over 30,000 views in the last month alone, which is not 30:1 – it’s more like 4000:1, assuming a steady viewing rate over the lifetime of the page.)

With this kind of disparity, the idea of collective intelligence as an integral part of Wikipedia’s model begins to fall apart. Yes, they depend on the collective intelligence of their editors, but the people editing make up a tiny percentage of the online community, which limits the potential of this kind of endeavor. Furthermore, this particular page has a very low threshold of entry to be considered an expert: have you seen the movie – yes or no? Have you read The Taming of the Shrew – also yes or no? A yes to one or both of these gives any person sufficient knowledge to contribute. Despite this, few people are participating in the creation of knowledge about this subject. Though Jenkins is full of optimism about the potential of collective intelligence and the shift in who is considered an “expert,” if very few people are contributing even to a page that requires very little knowledge to assist with, it just doesn’t work.

*I would provide a screenshot of the page’s revision history statistics, but the external site is down. However, I did view it yesterday, and if memory serves, it has been edited at least a couple of times a week since it’s creation, with a spike around the time the television adaptation came out.

Works Cited:

Graham, Jefferson. “Alex Mack’ Star’s Secret: Her Typical Teen Aura.” Larisa Online. USA Today, 04 Aug. 1995. Web. 08 Mar. 2015.

Jenkins, Henry. “WHAT WIKIPEDIA CAN TEACH US ABOUT THE NEW MEDIA LITERACIES (PARTS ONE and TWO).” Confessions of an AcaFan. N.p., 26-27 June 2007. Web. 07 Mar. 2015.

“3rd Rock from the Sun.” IMDb. IMDb.com, n.d. Web. 08 Mar. 2015.